Tell el-Daba, ancient Avaris

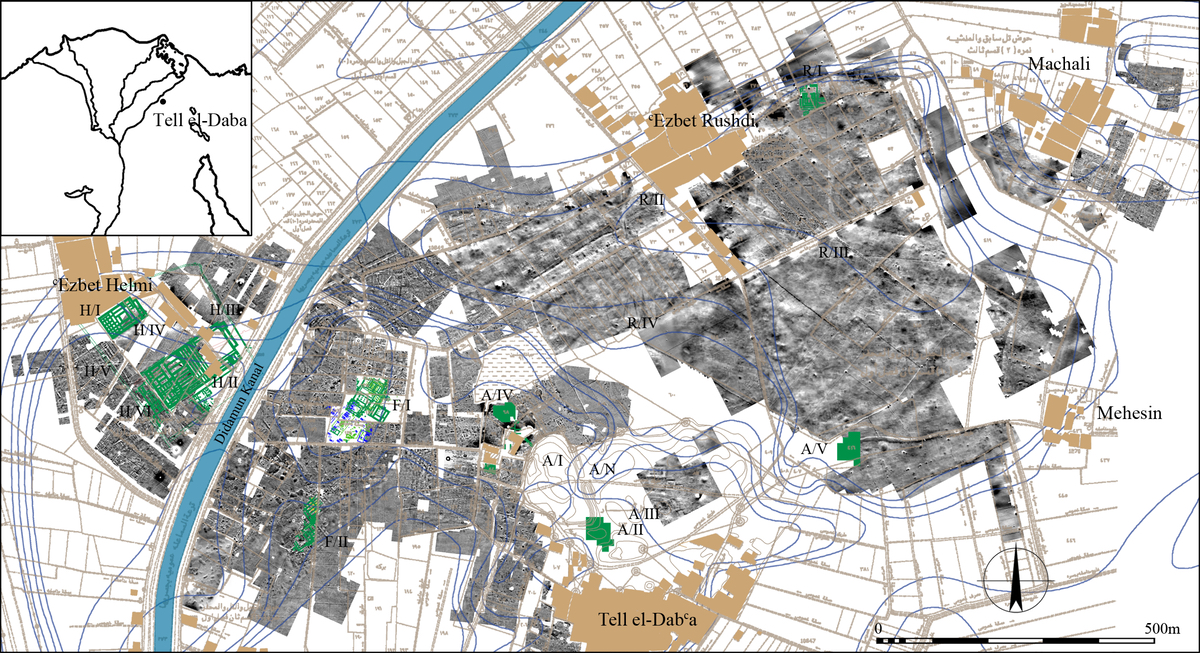

Figure 1: Geomagnetic map of TD with excavation areas marked in green (© copyright ÖAI/OREA archive).

Figure 1: Geomagnetic map of TD with excavation areas marked in green (© copyright ÖAI/OREA archive).

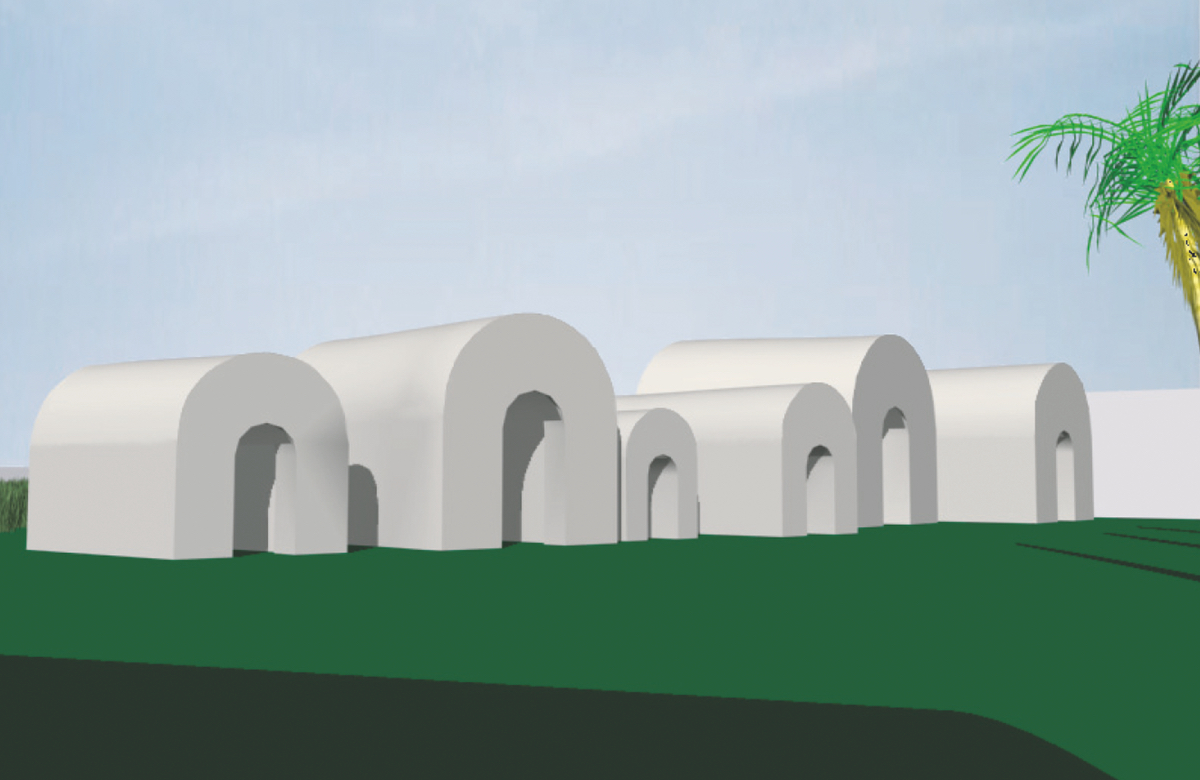

Figure 2: Reconstruction of early 13th dynasty tombs in area F/I (after Schiestl 2009, pl. XXXII/a).

Figure 2: Reconstruction of early 13th dynasty tombs in area F/I (after Schiestl 2009, pl. XXXII/a).

Figure 3: Two units of the planned settlement in area F/I – n/17 (M. Bietak, © copyright ÖAI/OREA archive).

Figure 3: Two units of the planned settlement in area F/I – n/17 (M. Bietak, © copyright ÖAI/OREA archive).

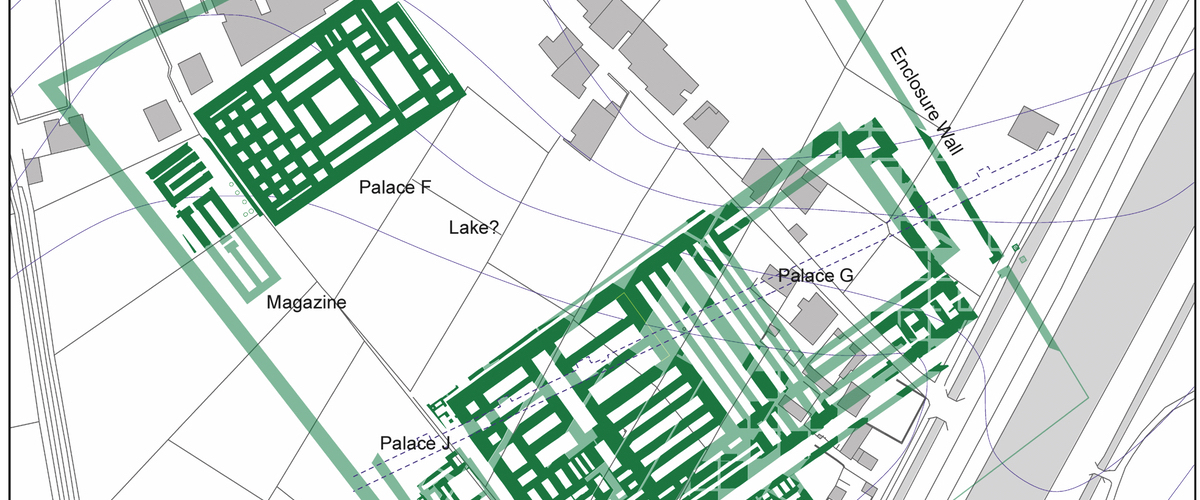

Figure 4: Plan of Palaces F, G and J and building L in Ezbet Helmi (plan by N. Math, © copyright ÖAI/OREA archive).

Figure 4: Plan of Palaces F, G and J and building L in Ezbet Helmi (plan by N. Math, © copyright ÖAI/OREA archive).

Figure 5: Area H/III palace G: Reconstructed Minoan-style wall paintings covering a wall or ceiling (drawing: M.A. Negrete Martinez © ÖAI/OREA)

Figure 5: Area H/III palace G: Reconstructed Minoan-style wall paintings covering a wall or ceiling (drawing: M.A. Negrete Martinez © ÖAI/OREA)

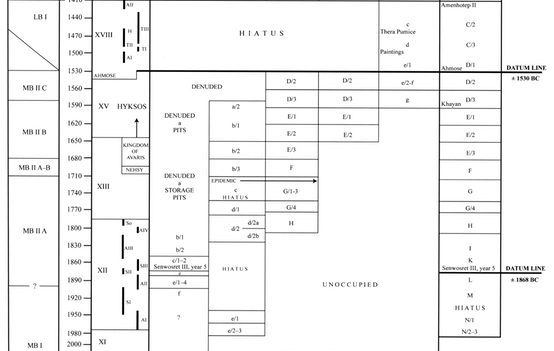

Table 1: Egyptian chronology and the phases of Tell el-Daba.

Table 1: Egyptian chronology and the phases of Tell el-Daba.

Image Gallery

The archaeological site of Tell el-Daba (TD), ancient Avaris, is situated on the eastern most of the five ancient Nile branches. Today the tell lies on the Didamun canal about 7 km north of the modern town Faqus in the Egyptian province of Sharkiyya (Fig. 1). Twenty phases of occupation at TD covered nearly 900 years of Egyptian history from the early 12th dynasty (c. 1980/70 BC)1 to the early Ptolemaic period.2 With a size of about 2,5 km2, it was one of the largest towns in the Eastern Mediterranean during the first half of the second millennium BC, when the site was one of the most important trading centres in this area.

From 1966 to date, with a short interruption due to the Arab-Israeli war from 1970‒1975, the site was investigated by the Austrian Archaeological Institute under the directorship of Manfred Bietak and his successor Irene Forstner-Müller. During that period, fieldwork took place in nine different areas, revealing a continuous stratigraphy from the early Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom3 (c. 1980/70 ‒ 1410 BC) (Fig. 1). With its mixture of Egyptian and Near Eastern Bronze Age culture, TD is important for chronological research in the region providing a link between Egyptian and Near Eastern chronologies (Table 1).4 Research on ancient Egyptian culture highly benefits from the excavations at Tell el-Daba as the site reveals evidence about all aspects of human life in an ancient harbour town, from temples and palaces to simple living quarters and cemeteries (Fig. 2).

At Tell el-Daba a planned settlement dating to the early Middle Kingdom (c. 1970 BC) is the first preserved archaeological evidence (Fig. 3). Founded at the eastern frontier of the Nile delta, it was built as a bulwark towards nomads from the east but at the same time was very likely used as a starting point for expeditions and as a trading outpost.5 After a short hiatus the town was extended and an enclosed settlement with houses arranged in insulae was built (c. 1900). Parts of these buildings were replaced by a temple founded by king Senwosret III in the first half of the Middle Kingdom (c. 1870 BC).6 After Senwosret III, people from the Near East who can be identified by Middle Bronze Age material culture settled in TD (c. 1825 BC). They conducted trade between Egypt and the Levantine coast and brought with them a new way of life and foreign beliefs. Evidence of these can be found in the architecture and burial traditions. In the following three centuries, a unique culture from traditional and incoming influences developed at TD, which was specific to the north-eastern Nile Delta and today is known as “the Hyksos culture”. The city of Avaris transformed to one of the most important ports in the Eastern Mediterranean and to a transshipment centre for Egypt.

During the last quarter of the Middle Kingdom (c. 1790/80 BC) a palace-like mansion was constructed with a garden and tombs which testify to the wealth of their owners.7 It seems that at the end of the Middle Kingdom (c. 1710/1700 BC), an epidemic struck the city and killed a large part of its population. In the following Second Intermediate Period, Tell el-Daba and a part of the eastern Nile delta separated politically from the Egyptian crown and formed the kingdom of Avaris. In one part of TD a cultic centre emerged with a series of temples of Near Eastern and Egyptian layouts surrounded by large cemeteries.8 Huge villas show the economic success of the inhabitants of Tell el-Daba at that time (c. 1700-1650 BC).9 The following period is known as the Hyksos period (c. 1650‒1530 BC). The names of the Hyksos kings, the “lords of the foreign countries” were documented by Manetho, an Egyptian priest, who wrote the first Egyptian history in the 3rd century BC. At Tell el-Daba the Hyksos kings constructed a huge palace of Near Eastern style.10 The residential areas were densely populated, with tombs partly built under the houses and used as family crypts.11 In this period the trade with the Levantine regions and other parts of Egypt declined,12 whilst exchange of goods with Cyprus boomed.13 After the conquest of Avaris by king Ahmose, the first ruler of the New Kingdom (c. 1530 BC), the Egyptians expanded the harbour and most likely based their naval fleet there.14 Large Egyptian-style palaces were now constructed at the area which is now Ezbet Helmi (Fig. 4). An important discovery was that the wall paintings in these palaces are very similar to those found in the palaces of Minoan Crete (Fig. 5). This shows a unique connection between Egyptian and Minoan culture at that time. A massive fortification wall was built on top of the palaces in the middle of the New Kingdom. Relicts of the Ramesside era are found all over Tell el-Daba, whether it be the massive enclosure wall of the Seth temple, vineyards, pits or slipper coffins. Finally, in the early Ptolmaic period the construction of tower houses, the ancient Egyptian equivalents to modern skyscrapers, represents the last chapter of the more than 17 centuries long history of Tell el-Daba.

Bibliography

-

E. Czerny, Tell el-Dabca IX. Eine Plansiedlung des frühen Mittleren Reiches, UZK 15 (Vienna 1999).

-

M. Lehmann, Die materielle Kultur der Spät- und Ptolemäerzeit im Delta Ägyptens am Beispiel von Tell el-Dabca (PhD Diss. University of Berlin, Berlin 2015).

-

K. A. Kitchen, The Strenght and Weakness of Egyptian Chronology – A Reconsideration, Ägipten und Levante 16, 2006, 293–308.

-

M. Bietak, Egypt and Canaan during the Middle Bronze Age, BASOR 281, 1991, 27–72.

M. Bietak, Antagonism in Historical and Radiocarbon Chronology, in: A. J. Shortland – C. Bronk Ramsey (eds.), Radiocarbon and the Chronologies of Ancient Egypt (Oxford 2013), 76‒109.

K. Kopetzky, Tell el-Dabca XX. Die Chronologie der Siedlungskeramik der Zweiten Zwischenzeit aus Tell el-Dabca, UZK32 (Vienna 2010).

-

E. Czerny, Tell el-Dabca IX. Eine Plansiedlung des frühen Mittleren Reiches, UZK 15 (Vienna 1999).

-

E. Czerny, Tell el-Dabca XII. „Der Mund der beiden Wege“. Die Siedlung und der Tempelbezirk des Mittleren Reiches von Ezbet Ruschdi, 2 vols., UZK 38 (Vienna 2015).

-

R. Schiestl, Tell el-Dabca XVIII. Die Palastnekropole von Tell el-Dabca. Die Gräber des Areals F/I der Straten d/2 und d/1, UZK 30 (Vienna 2009).

-

M. Bietak, Egypt and Canaan during the Middle Bronze Age, BASOR 281, 1991, 27–72.

V. Müller, Tell el-Dabca XVII. Opferdeponierungen in der Hyksoshauptstadt Auaris (Tell el-Dabca) vom späten Mittleren Reich bis zum frühen Neuen Reich, 2 vols., UZK 29 (Vienna 2008).

Forstner-Müller, Tell el-Dabca XVI. Die Gräber des Areals A/II von Tell el-Dabca, UZK 28 (Vienna 2008).

-

M. Bietak, Avaris. The Capital of the Hyksos (London 1996).

-

M. Bietak – N. Math – V. Müller, Report on the Excavation of a Hyksos Palace at Tell el-Dabca/Avaris, Ägipten und Levante 22/23, 2012/2013, 17–53.

-

I. Hein – P. Janosi, Tell el-Dabca, XI: Areal A/V, Siedlungsrelikte der späten Hyksoszeit, UZK 21 (Vienna 2004).

Forstner-Müller – C. Jeuthe – V. Michel – S. Prell, Das Areal R/III. Zweiter Vorbericht, Ägypten und Levante 25, 2015, 17–71.

-

K. Kopetzky, Tell el-Dabca XX. Die Chronologie der Siedlungskeramik der Zweiten Zwischenzeit aus Tell el-Dabca, UZK32 (Vienna 2010).

-

L.C. Maguire, Tell el-Dabca XXI. The Cypriot Pottery and its Circulation in the Levant, UZK 33 (Vienna 2009).

-

M. Bietak, Harbours and Coastal Military Bases in Egypt in the Second Millenium B.C. Avaris, Peru-nefer, Pi-Ramesse, in: H. Willems – J.M. Dahms (eds.), The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in Egypt (Mainz 2017), 53-70.